Methods

Positive viral tests indicate a current infection, while positive antibody tests indicate a prior infection. Other techniques include a CT scan, checking for elevated body temperature, checking for low blood oxygen level, and the deployment of detection dogs at airports.

Detection of the virus

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a process that amplifies (replicates) a small, well-defined segment of DNA many hundreds of thousands of times, creating enough of it for analysis. Test samples are treated with certain chemicals that allow DNA to be extracted. Reverse transcription converts RNA into DNA.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) first uses reverse transcription to obtain DNA, followed by PCR to amplify that DNA, creating enough to be analyzed. RT-PCR can thereby detect SARS-CoV-2, which contains only RNA. The RT-PCR process generally requires a few hours.

Real-time PCR (qPCR) provides advantages including automation, higher-throughput and more reliable instrumentation. It has become the preferred method.

The combined technique has been described as real-time RT-PCR or quantitative RT-PCR and is sometimes abbreviated qRT-PCR, rRT-PCR or RT-qPCR, although sometimes RT-PCR or PCR are used. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines propose the term RT-qPCR, but not all authors adhere to this.

Average sensitivity for rapid molecular tests were 95.2% (ranging from 68% to 100%) and average specificity was 98.9% (ranging from 92% to 100%) between test results of different company brands and sampling methods.

Samples can be obtained by various methods, including a nasopharyngeal swab, sputum (coughed up material), throat swabs, deep airway material collected via suction catheter or saliva. Drosten et al. remarked that for 2003 SARS, "from a diagnostic point of view, it is important to note that nasal and throat swabs seem less suitable for diagnosis, since these materials contain considerably less viral RNA than sputum, and the virus may escape detection if only these materials are tested."

Sensitivity of clinical samples by RT-PCR is 63% for nasal swab, 32% for pharyngeal swab, 48% for feces, 72–75% for sputum, and 93–95% for bronchoalveolar lavage.

The likelihood of detecting the virus depends on collection method and how much time has passed since infection. According to Drosten tests performed with throat swabs are reliable only in the first week. Thereafter the virus may abandon the throat and multiply in the lungs. In the second week, sputum or deep airways collection is preferred.

Collecting saliva may be as effective as nasal and throat swabs, although this is not certain. Sampling saliva may reduce the risk for health care professionals by eliminating close physical interaction. It is also more comfortable for the patient. Quarantined people can collect their own samples. A saliva test's diagnostic value depends on sample site (deep throat, oral cavity, or salivary glands). Some studies have found that saliva yielded greater sensitivity and consistency when compared with swab samples.

On 15 August 2020, the US FDA granted an emergency use authorization for a saliva test developed at Yale University that gives results in hours.

Viral burden measured in upper respiratory specimens declines after symptom onset.

Demonstration of a nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 testing

Demonstration of a throat swab for COVID-19 testing

A PCR machine

Isothermal amplification assays

Isothermal nucleic acid amplification tests also amplify the virus's genome. They are faster than PCR because they don't involve repeated heating and cooling cycles. These tests typically detect DNA using fluorescent tags, which are read out with specialized machines. CRISPR gene editing technology was modified to perform the detection: if the CRISPR enzyme attaches to the sequence, it colors a paper strip. The researchers expect the resulting test to be cheap and easy to use in point-of-care settings. The test amplifies RNA directly, without the RNA-to-DNA conversion step of RT-PCR.

Antigen

An antigen is the part of a pathogen that elicits an immune response. Antigen tests look for antigen proteins from the viral surface. In the case of a coronavirus, these are usually proteins from the surface spikes. SARS-CoV-2 antigens can be detected before onset of COVID-19 symptoms (as soon as SARS-CoV-2 virus particles) with more rapid test results, but with less sensitivity than PCR tests for the virus.

Antigen tests may be one way to scale up testing to much greater levels. Isothermal nucleic acid amplification tests can process only one sample at a time per machine. RT-PCR tests are accurate but require too much time, energy and trained personnel to run the tests. "There will never be the ability on a PCR test to do 300 million tests a day or to test everybody before they go to work or to school," Deborah Birx, head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, said on 17 April 2020. "But there might be with the antigen test."

Samples may be collected via nasopharyngeal swab, a swab of the anterior nares, or from saliva. The sample is then exposed to paper strips containing artificial antibodies designed to bind to coronavirus antigens. Antigens bind to the strips and give a visual readout. The process takes less than 30 minutes, can deliver results at point of care, and does not require expensive equipment or extensive training.

Swabs of respiratory viruses often lack enough antigen material to be detectable. This is especially true for asymptomatic patients who have little if any nasal discharge. Viral proteins are not amplified in an antigen test. According to the WHO the sensitivity of similar antigen tests for respiratory diseases like the flu ranges between 34% and 80%. "Based on this information, half or more of COVID-19 infected patients might be missed by such tests, depending on the group of patients tested," the WHO said. While some scientists doubt whether an antigen test can be useful against COVID-19, others have argued that antigen tests are highly sensitive when viral load is high and people are contagious, making them suitable for public health screening. Routine antigen tests can quickly identify when asymptomatic people are contagious, while follow-up PCR can be used if confirmatory diagnosis is needed.

Imaging

Typical visible features on CT initially include bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacities with a peripheral or posterior distribution. COVID-19 can be identified with higher precision using CT than with RT-PCR.

Subpleural dominance, crazy paving, and consolidation may develop as the disease evolves. Chest CT scans and chest x-rays are not recommended for diagnosing COVID-19. Radiologic findings in COVID-19 lack specificity.

Antibody tests

The body responds to a viral infection by producing antibodies that help neutralize the virus. Blood tests (serology tests) can detect the presence of such antibodies. Antibody tests can be used to assess what fraction of a population has once been infected, which can then be used to calculate the disease's mortality rate.

SARS-CoV-2 antibodies' potency and protective period have not been established. Therefore, a positive antibody test may not imply immunity to a future infection. Further, whether mild or asymptomatic infections produce sufficient antibodies for a test to detect has not been established. Antibodies for some diseases persist in the bloodstream for many years, while others fade away.

The most notable antibodies are IgM and IgG. IgM antibodies are generally detectable several days after initial infection, although levels over the course of infection and beyond are not well characterized. IgG antibodies generally become detectable 10–14 days after infection and normally peak around 28 days after infection. This pattern of antibody development seen with other infections, often does not apply to SARS-CoV-2, however, with IgM sometimes occurring after IgG, together with IgG or not occurring at all. Generally, however, median IgM detection occurs 5 days after symptom onset, whereas IgG is detected a median 14 days after symptom onset. IgG levels significantly decline after two or three months.

Average specificity of antigen tests is 99.5%, and average sensitivity is 56.8%, but there is extreme variation in sensitivity results (ranging from 0 to 94%) between test results of different company brands.

Genetic tests verify infection earlier than antibody tests. Only 30% of those with a positive genetic test produced a positive antibody test on day 7 of their infection.

Types

Rapid diagnostic test (RDT)

RDTs typically use a small, portable, positive/negative lateral flow assay that can be executed at point of care. RDTs may process blood samples, saliva samples, or nasal swab fluids. RDTs produce colored lines to indicate positive or negative results.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISAs can be qualitative or quantitative and generally require a lab. These tests usually use whole blood, plasma, or serum samples. A plate is coated with a viral protein, such as a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Samples are incubated with the protein, allowing any antibodies to bind to it. The antibody-protein complex can then be detected with another wash of antibodies that produce a color/fluorescent readout.

Neutralization assay

Neutralization assays assess whether sample antibodies prevent viral infection in test cells. These tests sample blood, plasma or serum. The test cultures cells that allow viral reproduction (e.g., VeroE6 cells). By varying antibody concentrations, researchers can visualize and quantify how many test antibodies block virus replication.

Chemiluminescent immunoassay

Chemiluminescent immunoassays are quantitative lab tests. They sample blood, plasma, or serum. Samples are mixed with a known viral protein, buffer reagents and specific, enzyme-labeled antibodies. The result is luminescent. A chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay uses magnetic, protein-coated microparticles. Antibodies react to the viral protein, forming a complex. Secondary enzyme-labeled antibodies are added and bind to these complexes. The resulting chemical reaction produces light. The radiance is used to calculate the number of antibodies. This test can identify multiple types of antibodies, including IgG, IgM, and IgA.

Neutralizing vis-à-vis binding antibodies

Most if not all large scale COVID-19 antibody testing looks for binding antibodies only and does not measure the more important neutralizing antibodies (NAb). A NAb is an antibody that defends a cell from an infectious particle by neutralizing its biological effects. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic. A binding antibody binds to the pathogen but the pathogen remains infective; the purpose can be to flag the pathogen for destruction by the immune system. It may even enhance infectivity by interacting with receptors on macrophages. Since most COVID-19 antibody tests return a positive result if they find only binding antibodies, these tests cannot indicate that the subject has generated protective NAbs that protect against re-infection.

It is expected that binding antibodies imply the presence of NAbs and for many viral diseases total antibody responses correlate somewhat with NAb responses but this is not established for COVID-19. A study of 175 recovered patients in China who experienced mild symptoms reported that 10 individuals had no detectable NAbs at discharge, or thereafter. How these patients recovered without the help of NAbs and whether they were at risk of re-infection was not addressed. An additional source of uncertainty is that even if NAbs are present, viruses such as HIV can evade NAb responses.

Studies have indicated that NAbs to the original SARS virus (the predecessor to the current SARS-CoV-2) can remain active for two years and are gone after six years. Nevertheless, memory cells including Memory B cells and Memory T cells can last much longer and may have the ability to reduce reinfection severity.

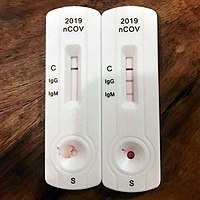

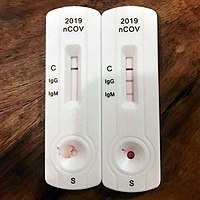

A Point of Care Test in Peru. A blood droplet is collected by a pipette.

Blood from pipette is then placed onto a COVID-19 rapid diagnostic test device.

The rapid diagnostic test shows reactions of IgG and IgM antibodies.

Other tests

Following recovery, many patients no longer have detectable viral RNA in upper respiratory specimens. Among those who do, RNA concentrations three days following recovery are generally below the range in which replication-competent virus has been reliably isolated.

No clear correlation has been described between length of illness and duration of post-recovery shedding of viral RNA in upper respiratory specimens.

Comments

Post a Comment